If you’re a wine enthusiast and opened your share of bottles, chances are you’ve encountered some that contain tartrate crystals, either as a visible sediment at the base of the bottle, or as a gritty lining on the bottom of the cork.

The crystals are white or clear in whites and rosé, but usually look black in red wines. They can be as tiny as a grain of sand or as large as a grain of flaky sea salt.

Some wines are more prone to tartrate development than others, but their raw materials are present in most wines. They are caused when a wine drops in temperature, leading some of the tartaric acid naturally present in grapes to bind with potassium in a solid, crystalline form known as potassium bitartrate.

Most wine drinkers understandably assume that crystals in wine are indications of spoilage, or even evidence of a manufacturing glitch, since these crystals can look like tiny shards of glass. But potassium bitartrate is 100% natural and completely harmless if ingested. In fact, when ground into powder, it is a common ingredient in baking, where it is called ‘cream of tartar.’

More important, the presence of tartrate crystals is not an indication that a wine is defective. Rather, they can be seen as a quality indicator, since crystallization occurs far more often in high-end wines than in mass-produced bulk products.

Finding these ”wine diamonds“ indicates that a winemaker has opted not to ”cold stabilize“ their wine, a process that does eradicate the possibility of crystals forming, but at the expense of stripping flavor and color from the wine.

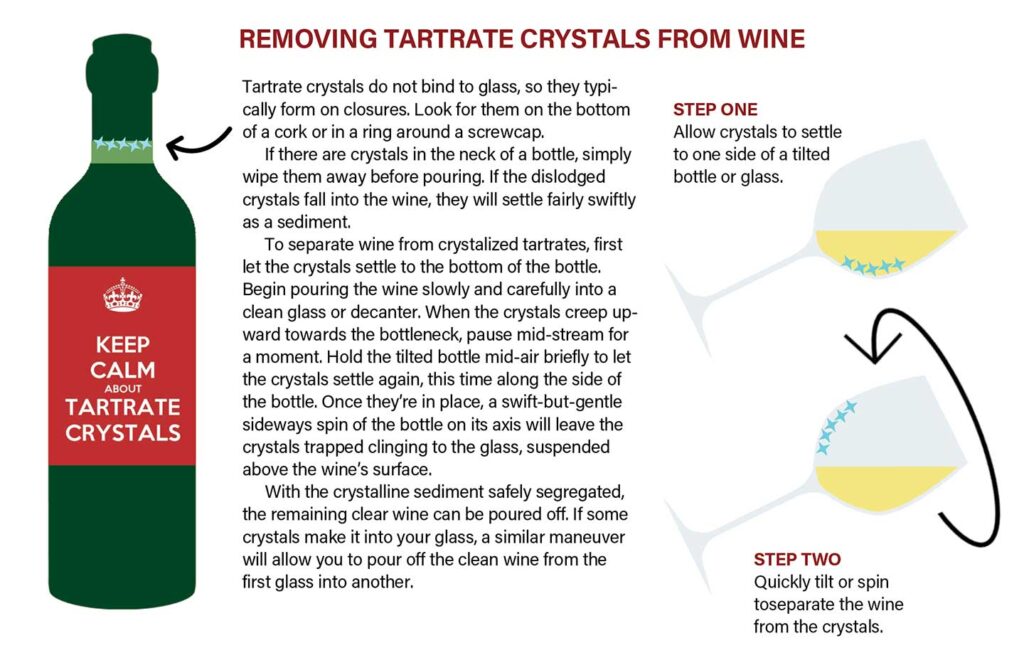

Tartrate crystals do not bind to glass, so they typically form on closures. Look for them on the bottom of a cork or in a ring around a screwcap.

If there are crystals in the neck of a bottle, simply wipe them away before pouring. If the dislodged crystals fall into the wine, they will settle fairly swiftly as a sediment.

To separate wine from crystalized tartrates, first let the crystals settle to the bottom of the bottle. Begin pouring the wine slowly and carefully into a clean glass or decanter.

When the crystals creep upward towards the bottleneck, pause mid-stream for a moment. Hold the tilted bottle mid-air briefly to let the crystals settle again, this time along the side of the bottle. Once they’re in place, a swift-but-gentle sideways spin of the bottle on its axis will leave the crystals trapped clinging to the glass, suspended above the wine’s surface.

With the crystalline sediment safely segregated, the remaining clear wine can be poured off. If some crystals make it into your glass, a similar maneuver will allow you to pour off the clean wine from the first glass into another.

Feature photo by Marco Bianchetti on Unsplash.

Marnie Old is one of the country’s leading wine educators. Formerly the director of wine studies for Manhattan’s French Culinary Institute, she currently serves as director of vinlightenment for Boisset Collection and is best known for her visually engaging books published by DK: the award-winning infographic Wine: A Tasting Course for beginners and the tongue-in-cheek He Said Beer, She Said Wine. Read her recent piece, Sorting Wine Into Flavor families.